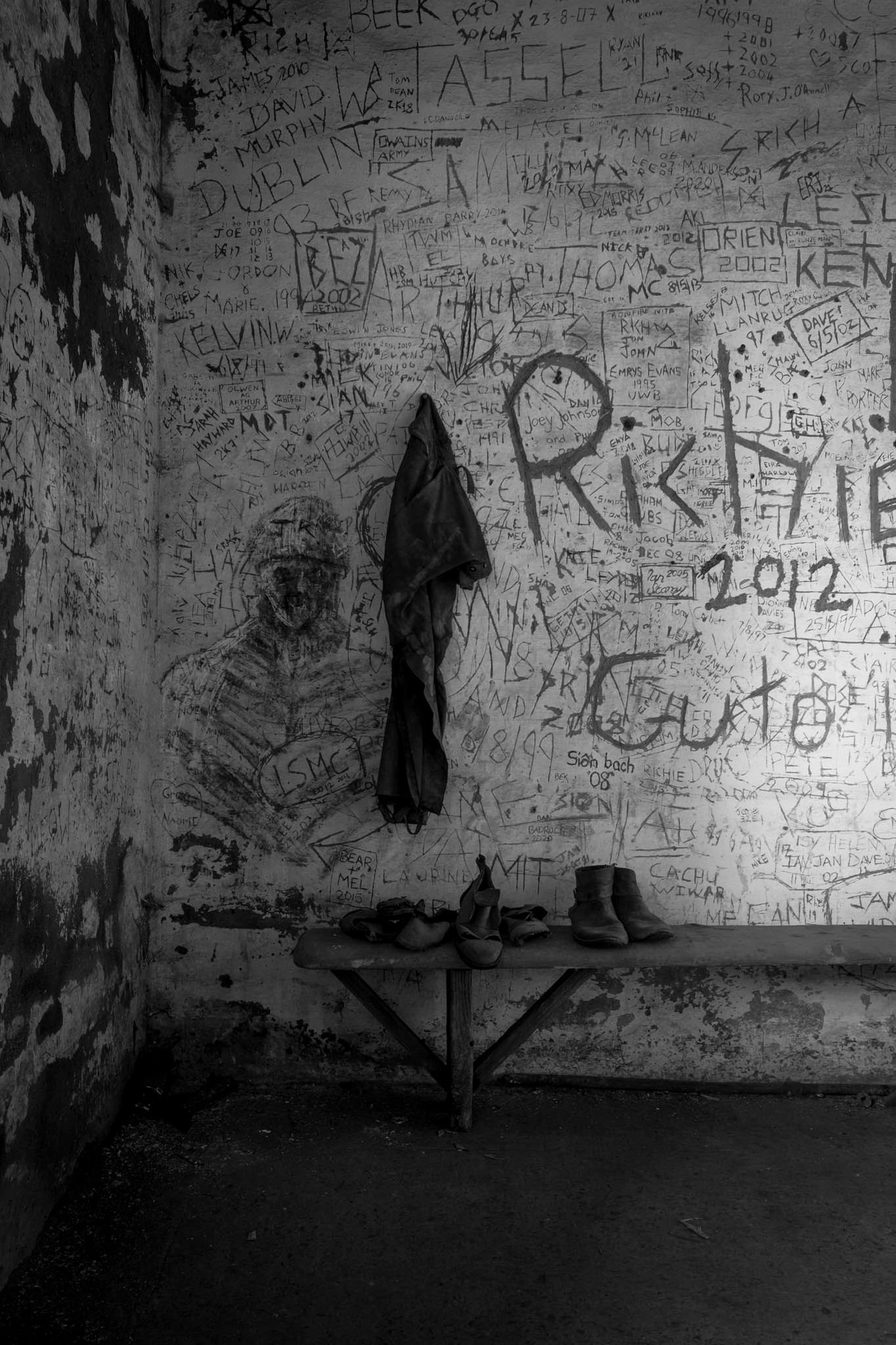

Dinorwic Quarry. North Wales

July 8, 2022Over the course of about 5 years, I have made numerous trips to one fantastic part of the UK, that spot is Dinorwic quarry.

This abandoned quarry is located to the North West of Snowdonia National park and attracts people for all sorts of activities, climbing, hill walking, cycling, caving and the odd photographer or 2, this is most likely due to its relatively easy access and amazing charm. I am still amazed each time I visit as the scale of the site, it just amazes me.

Over the course of my visits, I have had blistering sun, howling wind, horizontal rain and pea soup fog and I am still yet to see all of the site, so I think there will be a few more trips on the cards yet.

It goes without saying, this can be a very dangerous site and you do need to be careful while checking it out. If you are there for photography and are thinking of only stopping by for a few hours, don’t bother, wait till you have at least 4 or 5 hours spare as you will want to at least see a few bits of it, and then I would think you will be planning on your revisit again.

History of the site from Wiki:

Dinorwic quarry (/dɪˈnɔːrwɪɡ/ din-OR-wig; Welsh: [dɪˈnɔrwɪɡ]; also known as Dinorwig quarry) is a large former slate quarry, now home to the Welsh National Slate Museum, located between the villages of Llanberis and Dinorwig in Wales. At its height at the turn of the century, it was the second-largest slate quarry in Wales (and thus, the world), after the neighbouring Penrhyn Quarry near Bethesda.

Dinorwic covered 700 acres (283 ha) consisting of two main quarry sections with 20 galleries in each. Extensive internal tramway systems connected the quarries using inclines to transport slate between galleries.

Since its closure in 1969, the quarry has become the site of the National Slate Museum, a regular film location, and an extreme rock climbing destination.

The first commercial attempts at slate mining took place in 1787 when a private partnership obtained a lease from the landowner, Assheton Smith. Although this was met with moderate success, the outbreak of war with France, taxes, and transportation costs limited the development of the quarry. A new business partnership led by Assheton Smith was formed on the expiry of the lease in 1809 and the business boomed after the construction of a horse-drawn tramway to Port Dinorwic in 1824. At its peak in the late 19th century, “when it was producing an annual outcome of 100,000 tonnes”, Dinorwic employed more than 3,000 men and was the second-largest opencast slate producer in the country. Although by 1930 its working employment had dropped to 2,000, it continued in production until 1969. Quarrying Dinorwic quarry, showing major inclines, mills, levels, and tramways, and the Padarn Railway and Dinorwic Railway.

The slate vein at Dinorwic is nearly vertical and lies at or near the surface of the mountain, allowing it to be worked in a series of stepped galleries.

This is however not quite how the quarry developed. The first quarrying was spread across several sites: Adelaide, Allt Ddu, Braich, Bryn Glas, Bryn Llys, Chwarel Fawr, Ellis, Garrett, Harriet, Matilda, Morgan’s, Raven Rock, Sofia, Turner, Victoria, and Wellington.

This was a situation that lasted for many years, certainly until the mid-1830s. The 1824 railway brought transport problems. Produce from the upper quarries was not a problem, but Wellington, Ellis, Turner, Harriet, and Victoria quarries were all below the level of the railway. This was a problem solved in the 1840s when the lake level railway was built, and the quarry as we know it began to take shape. Adelaide quarry became a part of Allt Ddu, and Chwarel Fawr and Chwarel Goch became linked to it too. In the ‘Great New Quarry’, Raven Rock and Garret Quarries became one massive quarry, operating as an open hillside gallery quarry, with the lowest two levels being accessed by tunnels. Harriet, Morgans, and Sofia quarry are all still identifiable as separate pits today, whilst Braich quarry became a large working of three contiguous smaller pits. Below this, The galleries of Victoria and Wellington were joined along the hillside and continued downwards in two separate main workings: Wellington and Hafod Owen. Each was eventually to contain several small sinks too, some below lake level.

The current form of the quarry is little different from that of the time of the Great War, save for enlarging of the actual quarry faces and deepening of the sinks. Certainly, all the main inclines were in place, but very little was altered until closure.

The nearby Marchlyn quarry was opened in the 1930s to provide access to the main slate vein higher up the mountain.

The quarry closed in July 1969, the result of industrial decline and difficult slate removal.

During the 1950s/60s extraction had become difficult, because after 170 years of extraction many of the unsystematically dumped tips were beginning to slide into some of the major pit workings, and after an enormous fall in the Garret area of the quarry in 1966, production had ceased almost permanently. It was however decided that some final work could be done by clearing some of the waste from the Garret fall. This involved making an access road for more modern quarry vehicles across some of the terraces, to the rockfall. This amount of slate won by this method was small and all production stopped by 1969. At the Receiver’s instruction, a public auction was arranged, intended to pay off some of the quarry’s debts. The auctions were held on 12 and 13 December 1969. In the auctioneer’s national advertisement (in The Guardian 29 November 1969), the event was described as “An auction sale of machine tools and stocks, four Hunslet locos, and engine and boat fittings”. The locomotives referred to, lots 613–616, were “Dolbadarn”, “Red Damsel”, “Wild Aster” and “Irish Mail”. Before the bidding started, it was announced that Gwynedd County Council had placed a Preservation Order on the Gilfach Ddu workshops, and many items within it.